A blog dedicated to the protection of Canadian research participants and the accreditation of human research protection programs

Our research ethics boards aren’t the problem – the system wasn’t built to protect participants

Published January 13, 2026 in Healthy Debate: https://healthydebate.ca/2026/01/topic/research-ethics-boards-participant-protection/

Canada relies on independent accreditation and oversight for nearly every system in health care responsible for protecting people – from hospitals, community clinics and care facilities to laboratories and public health programs. The principle is straightforward: when human welfare is at stake, independent oversight is non-negotiable.

But that principle vanishes when it comes to protecting Canadians who participate in human research. Research Ethics Boards (REBs) – the bodies responsible for the ethical review of research and ensuring that it safeguards the individuals in it – operate with no national standards, no oversight and no accreditation at all.

This is not a bureaucratic oversight. It is the structural flaw underlying many of the ethical failures we have witnessed in Canadian human research in recent years, including the Prince Albert School Study (PASS).

Yet, whenever a research scandal emerges – a study that harms its participants, an experimental intervention marketed as care or a consent process that misleads people about risks – public blame lands squarely on the REB. It is the most visible procedural checkpoint in a system that offers only the illusion of oversight, and therefore the easiest entity to criticize.

But the uncomfortable truth is this: REBs are being held responsible for failures they cannot prevent. They are being asked to carry duties that belong to an oversight system Canada has never meaningfully built.

REBs are essential, but their mandate is narrow.

They review protocols before research begins, but they rarely (if ever) have direct contact with the people enrolled in studies.

They technically have authority to monitor active research, but they are rarely given the resources to do so.

They can suspend research, but few have the independence or institutional protection needed to act when powerful interests are involved.

Most importantly, the quality, capacity and independence of REBs vary widely across the country.

Canada has:

no independent oversight, and

no mechanism to ensure consistency or accountability.

In this environment, protection is not verified but presumed, which means responsibility almost exclusively defaults to REBs – committees that were never designed, resourced or empowered to carry such a burden alone.

This is why blaming REBs for systemic research failures misses the point. Canada’s response to research harms is reactive rather than proactive – we respond by faulting the REB, rather than by fixing the system – and a reactive posture cannot form the foundation of national protection, no matter how skilled or well-intentioned the people sitting on the ethics committees may be.

Real participant protection does not start at the REB deliberation table; it begins long before a protocol ever reaches it.

It depends on an institution’s entire ecosystem of oversight – the structures that determine:

how researchers are trained and qualified,

how conflicts of interest are identified and managed,

how privacy and data protections are implemented,

how contracts and indemnification are negotiated,

how quality is assessed and improved, and

whether the institution has the capacity and resources to conduct the research safely.

A responsible system recognizes that human research is inherently risky. Good intentions are not enough. Protection must be built into every layer of institutional practice from the moment a study is conceived – not just reviewed at a single meeting before it begins (as ethicist Michael McDonald observed in Is Anybody Minding the Store?).

Canada’s current governance structure lacks an integrated institutional framework to ensure research participant protection is consistent, proactive and accountable.

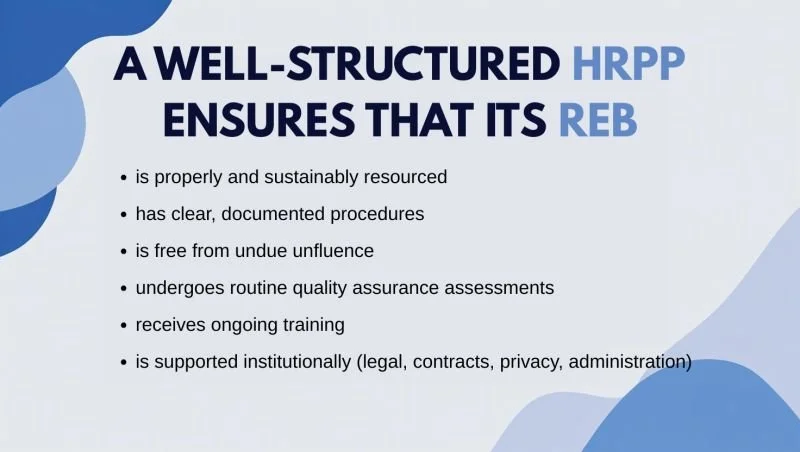

A Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) provides that framework. It ensures that ethics review, investigator qualifications, conflict-of-interest management, privacy protections, contracts, quality assurance and ongoing monitoring are aligned, coordinated and functioning long before an individual is approached for research participation.

Outside the research world, HRPPs may be unfamiliar. Inside it, they are recognized internationally as the backbone of research participant protection. In Canada, a standards-based HRPP accreditation program, grounded in multiple National Standards of Canada, is already in place. It offers the structure, independence and consistency our system has long needed, and it evaluates and strengthens the broader human research ecosystem.

The concept of HRPP accreditation is not new. Canada identified the need for system-level oversight more than two decades ago. However, we never developed a national mechanism to implement HRPP accreditation, leaving institutions without a coordinated framework for research participant protection.

In 2005, the National Council on Ethics in Human Research (NCEHR) published Options for the Development of an Accreditation System for Human Research Protection Programs, recommending that all institutions form HRPPs, that national standards be created and that a non-government body accredit them.

In 2008, the federally funded Sponsors’ Table Expert Committee reinforced these recommendations in its Moving Ahead report, adding costed implementation pathways. When no action followed, the Canadian 2012 report on Canada’s clinical trial infrastructure again urged the federal government to develop national standards and establish accreditation, echoing NCEHR’s earlier conclusions.

These Canadian analyses emerged in parallel with international developments, such as the creation ofAAHRPP in the United States. Today’s National Standards of Canada and HRPP accreditation system operationalize precisely what NCEHR and the federal Expert Committee called for: independent verification, institutional accountability and protections built into the entire human research enterprise – not just its REBs.

HRPP accreditation does not replace REBs or second-guess their judgments. It strengthens the system around them.

It introduces elements Canada has been missing for decades:

independent oversight,

uniform national expectations,

external validation of institutional practices,

continuous quality improvement,

transparent processes, and

participant-centred accountability.

It also aligns Canada with global norms. Countries with mature human research ecosystems use HRPP accreditation to ensure that protections are real, consistent and demonstrable. Canada remains an outlier, attempting to modernize research without modernizing the protections that must accompany it.

Accreditation is not a barrier to research. It is the mechanism that makes research safer, more efficient, more consistent and globally competitive.

Accreditation is not foreign to Canada. We already use similar models to protect animal welfare in research through the Canadian Council on Animal Care, and to assess the quality and safety of hospitals, clinics and care facilities through Accreditation Canada. These systems work because they rely on independent, standards-based evaluation – the very element missing from human research.

Canada now needs to take the next step: adopt HRPP accreditation nationally so that participant protection is no longer left to chance or dependent on where the research is conducted.

If Canada wants fewer ethical failures, fewer damaging headlines and fewer harms to the people who participate in research, the solution is clear: build the system REBs have always needed, rather than blaming them for the one they were never given.

Researchers and institutions deserve the clarity that comes with national standards.

REBs deserve the infrastructure that allows them to focus on ethics rather than compensating for system-level gaps.

And research participants – the people who contribute their bodies, data and trust – deserve protections as strong, rigorous and credible as those we already require for animals in research.

Until Canada makes this shift, research participants will continue to bear the consequences of a governance structure that was never designed to protect them.

Review of “Ethics on Trial” by Dr. Michael Owen

A pleasant surprise - and a meaningful one.

A colleague I deeply respect, Dr. Michael Owen, wrote a review of my book "Ethics on Trial", and it was published in Research Management Review.

He writes that the book “offers a stark reminder that after more than 40 years of developing codes, guidelines, and processes for the ethical conduct of research involving human participants, Canada’s splintered oversight regime continues to fail the most vulnerable among us…”

Seeing these issues taken seriously in a research leadership journal gives me some hope that we are finally beginning to talk about the difference between reviewing research and protecting the people in it.

If you’d like to read the review, it’s available here: https://www.ncura.edu/Portals/0/Docs/RMR/2025/Vol28_No1_BookReview_Owen.pdf

“My REB is Under-Resourced!”

This is one of the most common concerns I hear from REBs. And they’re right.

REBs are stretched thin and often expected to take on responsibilities well beyond their core ethical review function. 🐙

This isn’t just a resourcing issue - it’s a structural one.

The Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) is the overarching institutional system that ensures the ethical conduct of research involving humans. It encompasses far more than just the REB, and it’s where the concepts of institutional authority and accountability are operationalized and sustained.

Without an HRPP, responsibility for research participant protection defaults entirely to the REB - which was never designed to carry that responsibility alone. This creates a vacuum where the REB is left to train itself, monitor its own performance, and assume institutional duties, often without the necessary infrastructure or independence. That’s not just unsustainable - it creates potential conflicts of interest and undermines credibility.

Research participant protection is a shared responsibility. When institutions develop and maintain their HRPPs, REBs can focus on what they’re meant to do: ensure the protection of research participants through rigorous, independent ethics review.

Ooh là là…

… a box full of advocacy, hope, and purpose has arrived!

"Ethics on Trial" chronicles the untold stories of research participants in Canada and the system that failed to protect them. It’s a clarion call for change - grounded in national standards, oversight, accountability, and the collective will to do better.

Available this September at your favourite bookstore.

When Streamlining Becomes Risky: Why WHO’s Guidance Needs a Canadian Reality Check 🇨🇦

In 2024, the World Health Organization released its "Guidance for Best Practices for Clinical Trials", calling for a global shift toward more streamlined, risk-based regulation. The intent was sound: remove unnecessary delays and inefficiencies that slow down life-saving research. But in countries like Canada, where regulatory and ethical “bureaucracy” is often the only structural protection for research participants, that message needs nuance - and caution.

Since the dismantling of the National Council on Ethics in Human Research (NCEHR) in 2010, research participant protection has relied on two things: Health Canada’s regulatory inspections (which cover only a small fraction of regulated clinical trials) and institutional Research Ethics Boards (REBs) operating under the Tri-Council Policy Statement (TCPS 2) without any meaningful oversight or accountability. These mechanisms are essential - but patchy and unevenly applied across the country.

If we dismantle or streamline what little "oversight" we have, we risk leaving research participants - especially children, marginalized populations, and those in vulnerable settings - completely exposed.

That’s why HRPP accreditation is so critical. It’s the missing piece that aligns institutions with Canadian national standards (such as those developed by Canadian stakeholders through HRSO/ONRH) and embeds research participant protection into the operational culture of research, aligning with the TCPS 2. Far from being an obstacle, accredited HRPPs make ethical oversight more efficient, consistent, and accountable.

The World Health Organization is correct in calling for smarter regulation. But in Canada, we must be vigilant: “less bureaucracy” cannot mean “less protection.” HRPP accreditation remains our most effective safeguard against system-level failure - and the human tragedies that follow.

The Two Ryans

Two little boys named Ryan. One unregistered clinical trial. A tragedy that never should have happened.

At a major Canadian pediatric hospital (CHEO), two children received overdoses of an experimental drug in a research study that was never registered with Health Canada. Ryan Lucio, just four years old, died after receiving 25 times the correct dose of interleukin-2. Ryan Carroll, 18 months old, barely survived after receiving a 22-times overdose months earlier.

As Ryan Carroll's mother opined: "What if her son's adverse reaction had been reported to Health Canada? Would the overdose that cost Ryan Lucio his life have been prevented?"

This case remains a chilling reminder of what happens when clinical research lacks objective oversight and accountability, and why HRPP accreditation matters. No one, especially children, should pay the price for systemic failure.

Stories like this are central to my upcoming book: "Ethics on Trial – Protecting Humans in Canada’s Broken Research System" - coming this September.

Read more about the two Ryans here 👉 https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/deadly-clinical-trial-wasn-t-approved-by-health-canada-1.384348

On Single REB Review

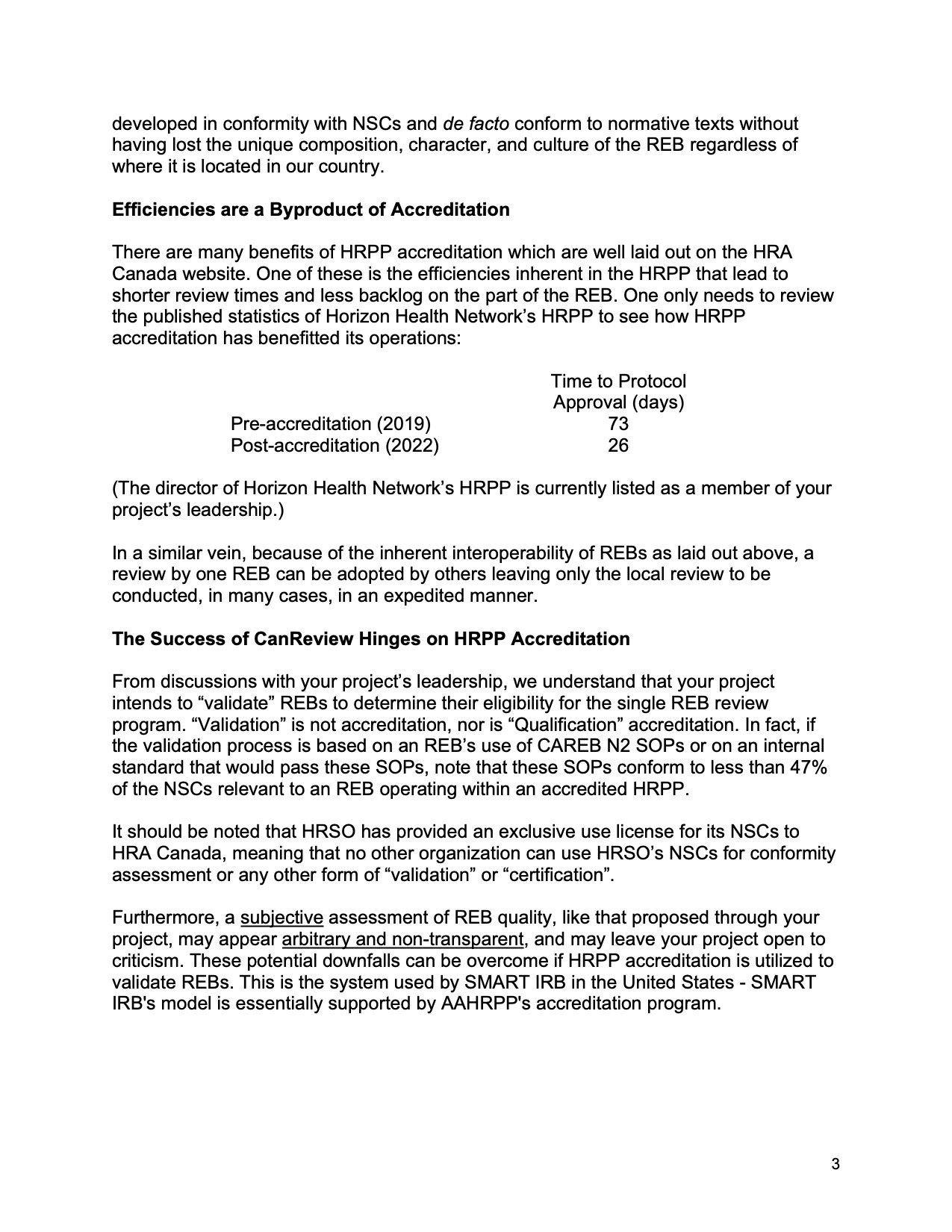

On February 5, our group sent a letter to CanReview expressing serious concerns about its plan to implement a single REB review model in Canada without a means to objectively and independently validate participating REBs. We outlined key gaps in its proposed approach and offered a proven, long-standing solution to assess REB quality: Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) accreditation.

HRPP accreditation is an internationally recognized, evidence-based program that provides an objective assessment of REB quality. It is also the backbone of SMART IRB, the single REB system operating in the United States. Today, over 1,350 institutions are members of SMART IRB—demonstrating both its credibility and broad adoption. To date, we have received no response to our letter.

Meanwhile, CanReview continues to move forward as though HRPP accreditation is not part of the conversation. CanReview does not have a mandate from Canadian stakeholders—no public consultation ever took place. Yet its unvalidated single REB model carries real consequences for research quality and research participant protection in our country. In the interest of transparency and accountability, we are now making our letter public (see below).

Our goal is not to criticize, but to advocate for a system that puts research participant protection and research integrity first. We encourage others in the research community to read our letter and speak up.

Ask CanReview why it is willfully ignoring HRPP accreditation—a solution with a 23-year track record of protecting research participants and upholding research quality and integrity! Time to put your oar in 🛶! Thank you.

The Deschamps Report

It all begins with an idea.

This month marks 30 years since the publication of the Deschamps Report (Report on Control Mechanisms for Clinical Research in Quebec).

The Deschamps Report was commissioned by the Quebec government following a significant ethical scandal in Quebec’s biomedical research sector—the “Affaire Poisson”. (Read more about this scandal and the significance of the Deschamps Report in my upcoming book → https://www.indigo.ca/en-ca/ethics-on-trial-protecting-humans-in-canadas-broken-research-system/9781459755970.html )

The Deschamps report provided a comprehensive evaluation of the ethical, legal, and operational frameworks governing clinical research. Most notably, it emphasized that research participant protection is a shared responsibility—a central theme that marked a significant evolution in our approach to ethical human research. It reframed human research participant protection not as a checklist or a gatekeeping function, but as a shared moral and structural commitment, requiring coordination, vigilance, and ethical integrity throughout the research lifecycle and across the entire research enterprise.

To our colleague Pierre Deschamps—thank you for reshaping the conversation. Your report’s insights continue to inform how we think about trust, transparency, and our shared duty to uphold human dignity in research. Your contribution remains profoundly relevant and has truly stood the test of time. Merci! ❤️

Assessing REB Quality

It all begins with an idea.

Saw a post yesterday where Western University’s director of research ethics and compliance touted "speed" as a key feature of CanReview’s proposed single REB review model. But since when has "speed" been a hallmark of rigorous research ethics review? How does this focus align with the primary role of an REB — which is safeguarding the rights, safety, and welfare of research participants?

The core mission of a Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) is protecting human research participants and ensuring responsible conduct of research through rigorous training, oversight, and accountability. Speed, efficiency, and harmonization are byproducts of HRPP accreditation.

In the U.S., the quality of an institution’s HRPP is the backbone of its single REB model – SMART IRB. The SMART IRB model reflects this priority, requiring institutions to undergo or initiate an assessment of their HRPP within five years before joining: “Within the 5 years prior to joining SMART IRB, the institution must have undergone or have initiated an assessment of the quality of its human research protection program (‘HRPP’).” HRPP accreditation is the most widely accepted assessment of HRPP quality - in Canada, this is performed by HRA Canada.

Single REB review must not be imposed on Canadians by a group unwilling to acknowledge the value of HRPP accreditation. Any discussion of single REB review in Canada must involve all stakeholders and be grounded in HRPP accreditation, just as SMART IRB requires. Let’s not reinvent the wheel — let’s ensure it’s moving forward responsibly based on a solid foundation.

Henri

It all begins with an idea.

Today, Henri would have been 95 years old.

Twenty years ago, his life was cut short while participating in a clinical study. Henri was what the drug industry calls a “normal healthy volunteer”—yet just 10 days into a bioequivalence trial at a test facility in Montreal, he suddenly collapsed and died.

His story is one of many that reveal the hidden human cost of research. It also inspired me to write "Ethics on Trial – Protecting Humans in Canada’s Broken Research System" (Dundurn Press, 2025).

Learn more about Henri and others whose experiences demand our attention: https://www.indigo.ca/en-ca/ethics-on-trial-protecting-humans-in-canadas-broken-research-system/9781459755970.html .

The Prince Albert School Study

It all begins with an idea.

The shocking revelations in CBC's investigation of the Prince Albert School Study (PASS) remind us that Canada needs to adopt HRA Canada's independent, objective accreditation program for human research. Without accreditation, human research ethics violations will continue unchecked.

This entire tragedy would have been prevented had the university developed a functional Human Research Protection Program. In an HRPP, the role of its leadership is clearly defined and monitored. The HRPP could have even been accredited which would have provided assurance by an independent third party that the HRPP was working properly.

A simple, cost-effective solution to prevent horribly harmful outcomes.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/saskatchewan/ethics-research-canada-privately-funded-1.7393063